- Home

- /

- Cognitive Psychology

- /

- Metacognition and Decision Making

When faced with ambiguous situations, people tend to change their behavior by monitoring their mental state and corresponding to their feeling of confidence (Nelson, 1996). Linked to hierarchical cognitive layers and self-awareness, this ability of an individual to self-regulate uses not only the individual’s knowledge but also the knowledge about knowledge to make an informed decision (Nelson & Narens, 1994). This highly sophisticated human trait of executive functioning (Metcalfe & Kober, 2005) can be faulty under uncertain conditions and it is the responsibility of the product designer to provide ways to support the user.

Knowledge about Knowledge

Metacognition, a level of thinking that engages active control over cognitive processes used in learning (Livingston, 2004), includes three components: Metacognitive Knowledge containing what people know about themselves and others as information processors; Metacognitive Experiences containing conscious occurrences pertaining to any cognitive endeavor; and Metacognitive regulation that helps people control their learning through activities which regulate cognition and experiences (Flavell, 1979). With viewpoints of variables that interact in different ways to affect the progress and result of a cognitive process, Metacognitive Knowledge in the long-term memory can be activated either intentionally by a memory search or automatically by retrieval cues (Koriat, 1997) to access: Declarative Knowledge, factors that can influence one’s performance (Schraw, 1998); Procedural Knowledge, heuristics and strategies that help in performing tasks automatically (Pressley, Borkowski, & Schneider, 2010); and Conditional Knowledge, allocation of resources that allow strategies to be effective (Garner, 1990). Cognitive and Metacognitive strategies may overlap with a distinction that the former helps an individual achieve a particular goal while the latter, usually preceding or following the former, ensures that the goal has been reached (Livingston, 2004). Both of these strategies might be invoked based on Metacognitive Experiences that occur before, after or during a cognitive process that simulates careful and conscious thinking (Flavell, 1979).

These components of metacognition are linked through Regulation which involves planning the appropriate selection of strategies and allocation of resources; monitoring the awareness of comprehension and task performance; and evaluating the final result of a task and its efficiency which can include re-evaluating the strategies used (Jacobs & Paris, 1987). Using an object-meta level distinction of cognition, Nelson and Narens (1994) separated retrospective and prospective monitoring where the latter is sub-divided in terms of the future state of the process being monitored into Ease-of-learning judgments, predicting what and how to learn (G. Seamon & Virostek, 1978; Underwood, 1966); Judgments of Learning, predicting the performance of recently studied items; and Feeling-of-knowing judgments, predicting whether a given item will be remembered in a retention test (Nelson, Gerler, & Narens, 1984). Although the neurological basis for this skill is undetermined, it is certain that this capacity varies across individuals and can be transferred to qualitatively diverse working memory tasks (Fleming, Weil, Nagy, Dolan, & Rees, 2010; Kornell, Son, & Terrace, 2007).

Decision Making and Selective Perception

One such task is decision making, where a single option is chosen after perceiving and evaluating a lot of information depending on multiple factors including the degree of uncertainty, time, familiarity, and expertise (Proctor, Zandt, & Zandt, 2018). Normative theories of decision making rely on how much an outcome is worth to the decision maker taking into account the probabilities of various alternatives and their utilities. It is derived from an optimal framework based on axioms (Salvendy, 2012). One such holistic way of decision making, Expected-utility theory is intended to describe how people would behave if they followed the requirements of rational decision making (Von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1947). However, the paradoxes of rationality in real life conditions led to the development of descriptive models that include the concept of Bounded Rationality where a decision maker bases decisions on a simplified model of the world (Simon, 1955). The process of decision making begins with the decision maker seeking cues from the environment through selective attention guided by the long-term memory. However, systematic biases during perception may affect the evidence accumulation stage since people are not very good at perceiving randomness in the environment as they perceive outliers to be significant trends (Tversky & Kahneman, 1971). Furthermore, the absence of cues may not be very evident to normal people, unlike good decision-makers who leverage strong metacognitive skills to be aware of the missing cues and gather these cues before making a firm situational analysis (Orasanu & Fischer, 1997). Moreover, the evidence that people generally do not show better decision making abilities as the number of information sources increase demonstrates the limitations of human attention and working memory for simultaneously integrating multiple cues (Schroeder & Benbasat, 1975). To add to it, cues carrying lower evidence or value for a hypothesis are weighted higher than others during integration if they are more salient (Payne, 1980) and cues carrying higher evidence for a hypothesis that is difficult to interpret are underweighted or sometimes ignored during integration (Johnson, Payne, & Bettman, 1988).

Heuristics, Hypothesis and Situational Assessment

Cue integration through correlation and expectancy provides possible hypotheses by leveraging past experiences from the long-term memory and leads to several unique heuristics further clarified by scripts (Nooteboom, 2005). The representativeness heuristic states people tend to match an observed pattern against few similar patterns learned from past experience invariant of weak or absent cues and choose the closest hypothesis or diagnosis (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Thus, people tend to choose salience of cues which is readily accessible over their reliability which is abstract (Griffin & Tversky, 1992; Kahneman & Frederick, 2002). The Availability heuristic states that people typically invite more available hypothesis taking into account the frequency, recency, simplicity, prior probability, and elaboration of an experience or event in the long-term memory (Schwarz & Vaughn, 2002). Furthermore, both availability and accessibility are associated with the idea of attribute substitution where certain effort-demanding tasks used by the working memory reliant analytical decision system (Type 2) are substituted by highly accessible processes used by the automatic and intuitive holistic decision system (Type 1) in experts when resources are scarce (Hammond, Hamm, Grassia, & Pearson, 1987; Kahneman, 2003). The Anchoring heuristic states that people tend to favor the initially chosen hypothesis due to factors that include primacy in memory and recency effect in cue integration when cues bearing evidence of multiple hypotheses arrive over time (Hogarth & Einhorn, 1992). Preventing people to encode and process cues that support a contradictory hypothesis, the Confirmation bias complements Anchoring by describing the tendency of people to interpret ambiguous cues in favor of the tentatively held belief through “cognitive tunnel vision” (Hogarth & Einhorn, 1992). In contrast, the effort and cognitive resources required for meticulous decision analysis deplete over time affecting decision accuracy. Thus, people tend to choose strategies that are less taxing due to decision fatigue (Royal et al., 2006).

Choice of Action

When the probability of all outcomes are certain, people may dissect each outcome by weighted attributes and use heuristics like Elimination-by-Aspects, where outcomes that do not fall within a required attribute criterion range are eliminated through consequent elimination starting from the most important attribute, saving cognitive effort depletion due to decision fatigue (Tversky, 1972). When faced with multiple attributes, people tend to use the rule of satisficing where only the most salient dimensions are considered and this tendency is even greater under stress and time pressure (Svenson & Maule, 1993). When faced with uncertain outcomes after isolating shared properties, people underweight lower probable options compared to options with higher probability leading to risk aversion and the isolation effect which produces inconsistent preferences when the same choices are presented in different forms (Kahneman & Tversky, 2012). Furthermore, if similar conditions to a previous experience are confronted, then a direct retrieval approach of using the same option may be used and sometimes coupled with a mental simulation anticipating consequences of an option (Klein & Crandall, 1995). Sometimes people choose short term gains rather than delayed greater gains (Rodriguez, Mischel, & Shoda, 1989) and also change their preference based on how the option is framed (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). Critical to the process of decision making and achieved through meta-cognition, Confidence influences an individual’s ability to seek more information, jump into action, or plan for alternatives in case of a wrong assessment and is often observed to be unrealistically high due to overconfidence bias (Nickerson, 1998).

Product Review

The target of this product review is the Credit card page of American Express (Amex), an American multinational financial services corporation.

Context

Vinod is an international student who is pursuing a master’s program in the United States of America and he has just entered the country a few weeks ago. After his initial research regarding the banking and financial services in the new country, he is certain that maintaining a good credit score will make it easier to rent apartments and obtain insurance benefits during his stay. Furthermore, as an added advantage he believes a good credit score would help him avail good cashback offers. However, Vinod is not very confident about using credit cards because of a memorable event in the past where he was charged a hefty annual fee during the second year of credit card service even though the issuer had issued a card that does not involve an annual fee. Thus, Vinod’s primary attributes while selecting a new credit card based on descending order of importance include:

1) No annual fee irrespective of the duration of usage and the amount spent through the card.

2) A good cashback for every transaction made using the credit card

With this context in mind, Vinod starts searching for a credit card on the website of American Express. The credit card page can be divided into five sections (refer Fig 1): High-level filtering tab section (red dashed rectangle), featured cards section (green dashed rectangle), browse all cards section (purple dashed rectangle), check for pre-qualified offers section (blue solid filled rectangle), and Amex details section (last section in the bottom).

High-level filtering tab

Positive. This section provides thematic cues to Vinod which act as attributes that help in filtering the 18 credit cards offered by Amex. The cues are easy to understand, equally salient and limited in number to guide normal decision makers. Furthermore, the dropdown of attributes under “More Categories” caters to holistic decision makers who may look at other attributes beyond the default ones.

Negative. This tab element does not allow Vinod to click more than one option simultaneously that can help him use the Elimination by Aspects strategy for decision making. Specifically, Vinod would ideally click on both “No Annual Fee” and “Cashback” expecting the result to have credit cards with no annual fee, sorted based on cashback. Thus, consider a better interaction by including elements that help users to filter and prioritize by the most important attributes.

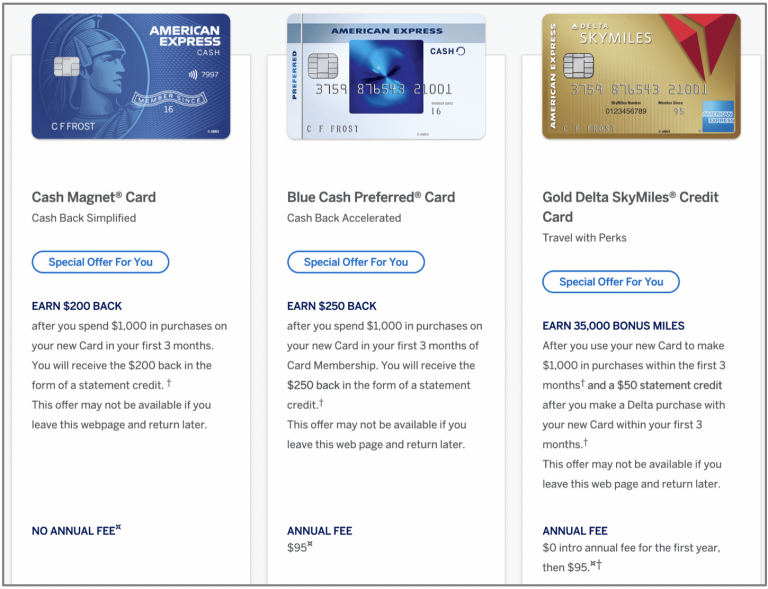

Featured cards section

This section features three cards that cause an Anchoring effect in Vinod’s mind as he analyzes all the cards. To supplement this effect, each card is highlighted with a maximized picture and the text “Special offer for you” makes it even more salient and personalized leading to salience bias. Moreover, the text “EARN $200 BACK” is more salient than the rest of the sentence “after you spend $1000”, implying the use of Framing effect to highlight the cashback rather than the expense. In contrast, the text “This offer will not be available if you leave this page and return later” adds time pressure to the decision maker. The salience of headers signifying cashback and annual fee suggest correlation of cues and, in this context, leads to Representativeness effect as Vinod’s past experience with credit cards defines these specific attributes as important factors for the decision. Furthermore, the annual fee description for the third featured card (rightmost) reads “$0 intro fee for the first year, then $95” and helps Vinod discard this option straight away through the elaborate memories of his past experience.

Positive. The designer of this page seems to have included certain aspects that favor these cards from the rest during the decision-making process by leveraging principles that influence human decision making. As design ethics is not a part of this product review, the author of this paper has considered his judgement on ethics out of scope.

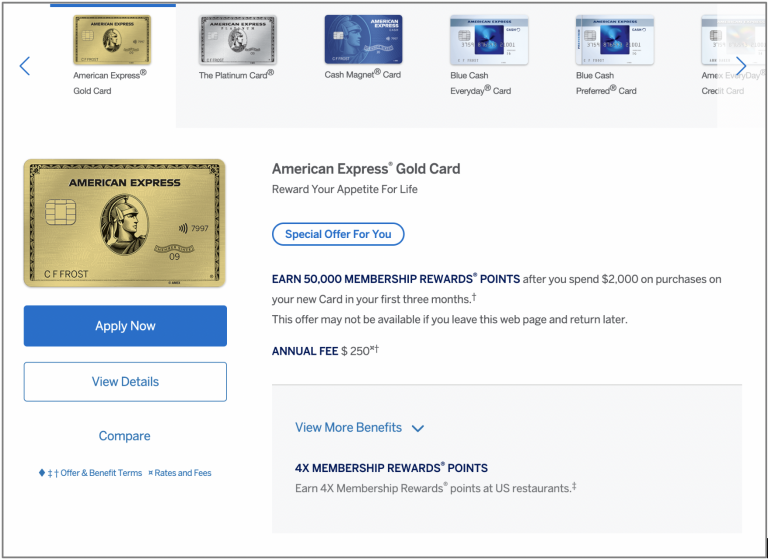

Browse all cards section

This section gives Vinod the ability to browse all of the 18 cards offered by Amex. The description of each card emphasizes on short-term gains over the long-term annual fee dedication.

Positive. This section allows holistic decision makers to compare credit cards by every attribute. Furthermore, comprehensive information regarding each card is available when the user clicks on “View Details”.

Negative. The section does not allow the decision maker to filter options through weighted attributes. Thus, Vinod would have to look at the brief description of each of the 18 cards before he thinks of comparing a few of them. This process will use his cognitive resources and he might choose the Satisficing strategy by choosing any one of the recently viewed cards which satisfies most of his criteria.

Check for pre-qualified offers

Positive. Unlike Vinod who is yet to have a credit score, other users who already have a credit score might fear that their score would be affected if they apply for a credit card and do not qualify for it. This section instills confidence to these decision makers which can, in turn, prevent risk aversion.

Negative. This section is at the bottom of the page and may not be noticed by users. Since this section would provide crucial information to users, consider placing this section at the top.

Amex details section

Positive. The last section of the screen caters to people who are uncertain of their choice to go ahead with Amex and provides details that, in turn, strengthen their confidence.

Considering all the biases and heuristics involved in the decision-making process, it is evident that humans may not think rationally in every context, thus it is the duty of the product designer to guide the decision maker with the right information at every step of the process and build confidence.

References

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Fleming, S. M., Weil, R. S., Nagy, Z., Dolan, R. J., & Rees, G. (2010). Relating Introspective Accuracy to Individual Differences in Brain Structure. Science, 329(5998), 1541–1543. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1191883

- Seamon, J., & Virostek, S. (1978). Memory performance and subject-defined depth of processing. Memory & Cognition, 6(3), 283–287. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03197457

Garner, R. (1990). When Children and Adults Do Not Use Learning Strategies: Toward a Theory of Settings. Review of Educational Research, 60(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543060004517

Griffin, D., & Tversky, A. (1992). The weighing of evidence and the determinants of confidence. Cognitive Psychology, 24(3), 411–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(92)90013-R

Hammond, K. R., Hamm, R. M., Grassia, J., & Pearson, T. (1987). Direct comparison of the efficacy of intuitive and analytical cognition in expert judgment. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 17(5), 753–770. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.1987.6499282

Hogarth, R. M., & Einhorn, H. J. (1992). Order effects in belief updating: The belief-adjustment model. Cognitive Psychology, 24(1), 1–55.

Jacobs, J. E., & Paris, S. G. (1987). Children’s Metacognition About Reading: issues in Definition, Measurement, and Instruction. Educational Psychologist, 22(3–4), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1987.9653052

Johnson, E. J., Payne, J. W., & Bettman, J. R. (1988). Information displays and preference reversals. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 42(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(88)90017-9

Kahneman, D. (2003). Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics. American Economic Review, 93(5), 1449–1475. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803322655392

Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness Revisited: Attribute Substitution in Intuitive Judgment. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and Biases (1st ed., pp. 49–81). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808098.004

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2012). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. In World Scientific Handbook in Financial Economics Series: Vol. Volume 4. Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making (pp. 99–127). https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814417358_0006

Klein, G., & Crandall, B. W. (1995). The role of mental simulation in problem solving and decision making. Local Applications of the Ecological Approach to Human-Machine Systems, 2, 324–358.

Koriat, A. (1997). Monitoring one’s own knowledge during study: A cue-utilization approach to judgments of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 126(4), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.126.4.349

Kornell, N., Son, L. K., & Terrace, H. S. (2007). Transfer of Metacognitive Skills and Hint Seeking in Monkeys. Psychological Science, 18(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01850.x

Livingston, J. A. (2004). Metacognition: An Overview. 9.

Metcalfe, J., & Kober, H. (2005). Self-reflective consciousness and the projectable self. The Missing Link in Cognition: Origins of Self-Reflective Consciousness, 57–83.

Nelson, T. O. (1996). Consciousness and metacognition. American Psychologist, 51(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.102

Nelson, T. O., Gerler, D., & Narens, L. (1984). Accuracy of feeling-of-knowing judgments for predicting perceptual identification and relearning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(2), 282–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.113.2.282

Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1994). Why investigate metacognition. Metacognition: Knowing about Knowing, 1–25.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Nooteboom, B. (2005). Framing, attribution and scripts in the development of trust. Proceedings of Symposium on ‘Risk, Trust and Civility.

Orasanu, J., & Fischer, U. (1997). Finding decisions in natural environments: The view from the cockpit. Naturalistic Decision Making, 343–357.

Payne, J. W. (1980). Information processing theory: Some concepts and methods applied to decision research. Cognitive Processes in Choice and Decision Behavior, 95, 115.

Pressley, M., Borkowski, J. G., & Schneider, W. (2010). Cognitive strategies: Good strategy users coordinate metacognition and knowledge.

Proctor, R. W., Zandt, T. V., & Zandt, T. V. (2018). Human Factors in Simple and Complex Systems. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315156811

Rodriguez, M. L., Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1989). Cognitive person variables in the delay of gratification of older children at risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(2), 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.358

Royal, K. A., Farrow, D., Mujika, I., Halson, S. L., Pyne, D., & Abernethy, B. (2006). The effects of fatigue on decision making and shooting skill performance in water polo players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(8), 807–815.

Salvendy, G. (2012). Handbook of human factors and ergonomics. John Wiley & Sons.

Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003044231033

Schroeder, R. G., & Benbasat, I. (1975). An experimental evaluation of the relationship of uncertainty in the environment to information used by decision makers. Decision Sciences, 6(3), 556–567.

Schwarz, N., & Vaughn, L. A. (2002). The availability heuristic revisited: Ease of recall and content of recall as distinct sources of information.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884852

Svenson, O., & Maule, A. J. (1993). Time Pressure and Stress in Human Judgment and Decision Making. Springer Science & Business Media.

Tversky, A. (1972). Elimination by aspects: A theory of choice. Psychological Review, 79(4), 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0032955

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1971). Belief in the law of small numbers. Psychological Bulletin, 76(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031322

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. Retrieved from JSTOR.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458. Retrieved from JSTOR.

Underwood, B. J. (1966). Individual and group predictions of item difficulty for free learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71(5), 673–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023107

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1947). Theory of games and economic behavior, 2nd rev. ed. Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press.